“Separating the human Jesus from the myth.”

This was the ambitious task for a book published in 2007 titled Jesus for the Non-Religious.

The author did not say that God does not exist. Instead, he said that humans cannot adequately describe God. That’s why we have the word ineffable. God can only be experienced.

OK. So far, so good.

In Jesus, we have the perfect exemplar of human life lived fully—so thoroughly that all who experienced him believed him to be “a human portrait of the love of God.” Their experience of Jesus was so transforming that they tried to find thousands of ways to articulate it. But the experience of God is what mattered, not so much how they described it.

Next Question: Was Jesus divine?

Our writer says, “Yes and No.”

Yes, in the sense that Jesus revealed so fully and abundantly the love of God.

No, in the sense that we commonly use the term divine to describe something supernatural poured into a human. Many Christians may part company at this second point, but one hopes not without thinking seriously about what is trying to be said.

This took me two-thirds of the way through the book. The author had reached a point I could agree with—Jesus was the perfect embodiment of everything God intended human beings to be. It was an excellent place to end the debate.

Who is the author?

John Shelby Spong. Don’t stop reading.

Oh, good. You’re still here.

Spong is hard work. Especially for those who were Sunday schooled in “Bible-believing” churches. My 1950s Methodist education shaped my understanding of the King James version of the Bible as WRITTEN BY GOD—every word true, every sentence perfect—the Words of God.

It was a shock to discover my father was reading J.B. Phillips.

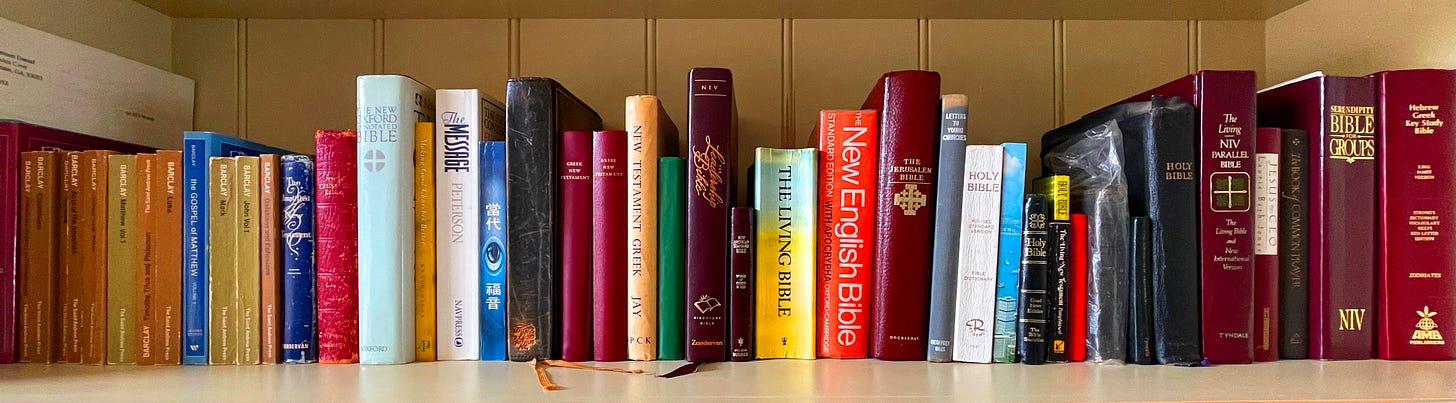

Now, I have a shelf of Bibles and as many commentaries. I also believe in the Divine Editor, who inspired the collecting, compiling and editing and continues to do so.

Back to Spong’s book

The third section of the book took an anthropological detour. It had only a tenuous link between his arguments in parts 1 and 2.

A chapter titled “Recognising the Sources of Religious Anger” attempted to explain the relationship between violence and religion. This is with apparent ignorance of, or perhaps intentional disregard of, the growing and rich scholarly work in this field, notably by Rene Girard.

Spong makes so many telling points that one wishes he and Girard had been able to sit and compare notes. The collaboration would have been so rich and valuable.

For example, Spong makes the common observation that “a cursory look at Christian history will provide ample evidence to support the conclusion that there is a very high correlation between theistic religion and killing anger.”

Therefore, religion causes violence.

But correlation and cause are not the same thing.

Spong says, “We… would rather live with an illusion than try to embrace reality.” Girard made a similar observation but concluded that violence causes religion.

Violence causes Religion.

Girard has shown, not merely as a speculation but as a well-documented characteristic of human society since the foundation of the world, that it is the other way around. As counterintuitive as it seems to modern sensibilities, it is violence that creates religion.

Through his anthropological and literary research, Girard showed that religion emerged as a feature of society’s scapegoating mechanism.

The search for, and the killing of, a scapegoat was discovered back in the mists of time as the most effective way to drain violence and conflict out of a community and, indeed, to create the unifying bonds of community. Girard went so far as to assert that this conflict-resolving character of scapegoating creates culture and, thus, communities.

Religion then emerged to recollect and renew the foundational scapegoating event and, at the same time, to justify and hide the reality.

Spong again gets close when he discusses Jesus as “the breaker of tribal boundaries” and “the breaker of prejudices and stereotypes.” His conclusions are correct. His road to these conclusions is not.

Jesus breaks down barriers, prejudices, and stereotypes by revealing the innocence of the scapegoat by becoming the perfect innocent scapegoat himself.

You see, the scapegoating mechanism only works if we believe the scapegoat is guilty. So long as we think the death of the scapegoat is justified, our anger, conflict and hostility are drained away by killing them.

The author of John’s gospel has Caiaphas, the High Priest, articulate the scapegoating mechanism with perfect logic, “You do not realise that it is better for you that one man dies for the people than that the whole nation perish.”

The death of the scapegoat creates community.

Is it any surprise that Luke’s gospel notes that after the crucifixion, “Herod and Pilate became friends—before this, they had been enemies”? As Luke points out later, in Acts 4:27, “Herod and Pontius Pilate met together … to conspire against your holy servant Jesus.”

Conspiracy against a common enemy continues to be one of the best examples of how the scapegoating mechanism creates unity. Nations are never more unified than when fighting a common enemy.

Witness the USA in the weeks following 9/11. Even the Dixie Chicks were scapegoated (fortunately temporarily for Country music lovers).

The insight Girard could have given Spong is this: Jesus is everything Spong says he is because his death unveiled the roots of violence within society.

Never before in human history has the victim of scapegoating violence so clearly been innocent.

Never before has the victim died—and then NOT died!

Never before has the victim been so forgiving in response.

Spong has done much more than many writers who attempt to reconcile modern scholarship with faith. He is often attacked for this, indeed scapegoated.

Instead, he deserves our appreciation. He has attempted to articulate what the experience of Jesus means in light of these new understandings.

His conclusions resonate with an analysis from the Girardian perspective, adding credibility to Spong and Girard’s approach to reconciling what we know with what we believe.